Highlighting organic alternatives transforming construction—without the hype.

The Material Shape of Tomorrow’s Neighbourhoods

In every city, the materials we build with whisper a story. Not just of structure, but of values. A home, a school, a corner shop — these are not neutral objects. They are public statements about our relationship with nature, history, and each other.

For decades, concrete and steel wrote that story. They spoke of speed, permanence, and control. But today, their legacy sits uncomfortably with the challenges we face. Carbon emissions, heat islands, brittle infrastructure in the face of climate change — these are not design flaws. They are the predictable results of a material culture that forgot to look both forward and inward.

Now, the conversation has begun to shift. Natural composites — materials made by combining plant-based or earth-based substances — are stepping forward. Not to replace every modern tool, but to rebalance the dialogue between building and landscape. In this, bamboo is often the headline. But it is not the whole story.

The Case for Going Beyond Bamboo

Bamboo grows fast. It stores carbon. It supports livelihoods in many tropical regions. But in some discussions, it has become shorthand for sustainability itself. That is dangerous. No single material carries all answers. When sustainability becomes branding, planning loses depth. We must widen our view.

In West Africa, builders have long shaped homes from laterite, a porous, iron-rich stone formed in tropical soil. When cut and left to dry, it hardens in air. It insulates well and suits humid climates. Its thermal mass — the ability to store heat — makes it useful in passive cooling. Planners in places like Guinea or Nigeria do not need to import ideas from abroad when the earth itself offers workable solutions.

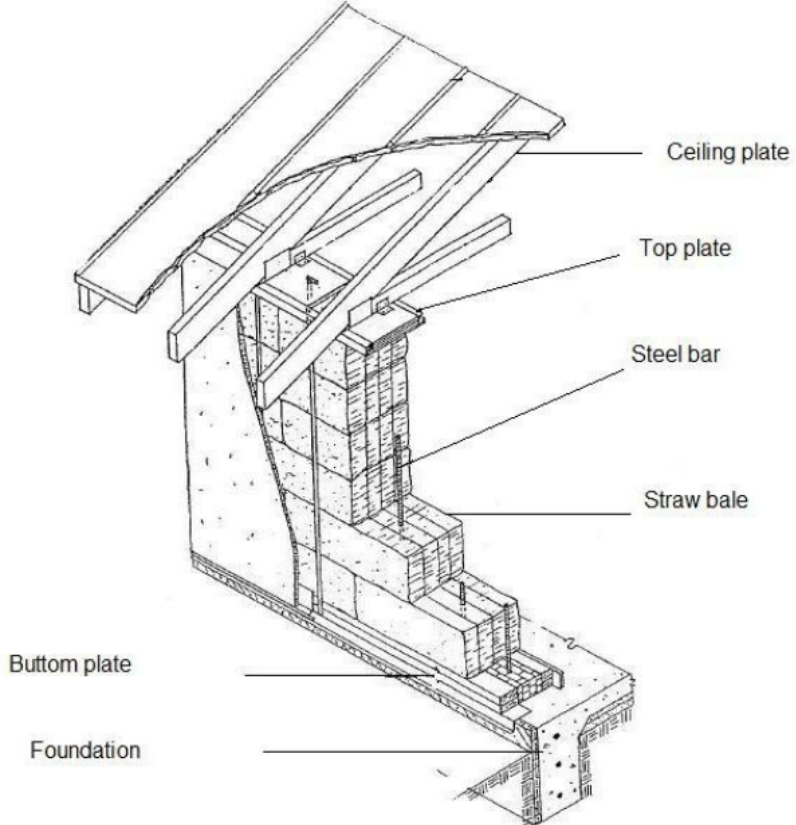

Meanwhile, in parts of Europe, interest grows in hempcrete — a blend of hemp fibres, lime, and water. It breathes, it resists fire, and it composts at the end of its life. It does not bear heavy loads, but used in walls with timber frames, it offers warm, dry buildings with low embodied carbon — the total emissions it takes to make, move, and fit a material. Treated straw bales have many of the qualities of hempcrete.

Policy Must Move with Practice

Materials do not change cities on their own. Planning law, building codes, and investment choices shape what is possible. If regulations still favour concrete over clay or penalise low-carbon alternatives, progress slows. Policymakers must make space in the rulebook for materials rooted in ecology.

Some hesitate. They see concrete and steel as the only path to certainty — the known quantities in risk-averse spreadsheets. The cost of experimenting, they say, is too high. But no one is calling for their immediate eradication. Steel and concrete still serve critical roles, particularly in infrastructure and large spans. The real opportunity lies in hybrid models — designs that weave sustainable composites into structures to reduce the overall environmental burden.

Figure 1 – Reproduced from Ashour and Wu (2011), Chapter 12 in Advances in Materials Science Research, Vol. 6, Nova Science Publishers, ISBN 978-1-61209-745-9. Copyright © 2011 by the respective authors and publisher. Reproduced here under fair dealing provisions for non-commercial, educational use. No further reproduction or distribution without permission.

Walls of earth and timber. Floors supported by bamboo-reinforced slabs. Roofs shaded with compressed straw panels. These solutions are not radical. They are incremental, rational steps that reduce carbon without shocking the system.

Education helps. Policymakers must understand that some organic composites offer reliable strength. Bamboo has a high tensile strength — it can resist pulling forces, like steel. Earth-based materials such as compressed stabilised earth blocks handle compressive loads well — they hold weight from above, like stone or concrete.

When planners and decision-makers gain confidence in these properties, they unlock new possibilities. Training, demonstration projects, and long-term studies all play a role in shifting mindsets.

Subsidies and incentives can drive this shift. Public building contracts — schools, health clinics, social housing — must lead the way. A planner who commissions a hempcrete school or an architect who specifies locally sourced earth blocks does more than design a building. They anchor a new civic logic.

A Neighbourhood is Not a Machine

The urban planner should not think only in plots, pipes, and density. A neighbourhood is a moral act that hosts lives. It remembers histories. It must breathe, adapt, and feel rooted.

Using natural composites changes how streets feel. Walls made of compressed earth or bamboo panels do not reflect heat like concrete. They lower urban temperatures and speak of place, not of distant factories. Such construction invite local labour, reuse, and material care.

These choices shape not just carbon outcomes but civic rhythms. In Accra, a street built with laterite bricks and shaded by trees offers a cooler walk than one lined with asphalt and steel. In Bristol, a hemp-wrapped community hall holds warmth through long winters and connects its users to the farm that grew its walls.

Craft, Climate, and the Public Good

There is no one-size-fits-all material. The damp winters of Northern Europe demand breathability and insulation. The hot, dry spells of sub-Saharan cities need cooling and resilience. Yet across these regions, we see a shared need — for buildings that do less harm, and for policies that help good design rise.

Craft must return to the centre. Not nostalgia, but a forward craft — one that knows the soil, honours local economies, and leans on science without losing sight of people. Architects and planners must form alliances with farmers, builders, and ecologists. Together they must write new rules.

Looking Forward

We must stop asking whether natural composites can compete. That is the wrong question. The right one is: what kind of future do we want to build? One where buildings last without burdening the earth or one where materials carry memory, reduce harm, and restore balance?

Beyond bamboo lies a world of options. But more importantly, beyond bamboo lies a shift in mindset — one that sees neighbourhoods not as machines, but as living systems shaped for and by the public good.

Bamboo Urbanism: The Proven Way to Reclaim Flood-Prone African Streets

Not every African city began beside water. Many Sahelian settlements grew around wells, wadis and…

Human-Scale Neighbourhoods: The Proven Way to Build Strong, Sustainable Cities

Urban life thrives when its parts fit the human body and mind. Streets, squares and…

Bamboo Cluster Neighbourhoods: The Proven Way to Advance African Eco-Urbanism

Last week’s post revived sociability through human-centred streets. This post shifts towards the home. I…

Human-Centred Streets: The Proven Way to Reclaim African Urban Sociability

Every city tells a story through its streets. They reveal how people live, how they…

Biophilic Design: The Proven Way to Shape Sustainable African Communities

A city breathes when its architecture remembers nature. Too often, our modern buildings forget this….

Open-Source Urbanism: The Proven Way to Empower African City Builders

Urban design cannot succeed if knowledge remains locked behind bureaucracy. The tools of planning must…