The future of our cities will not be delivered to us. It must be built—together.

Across West and North West Africa, climate stress, rapid urbanisation, and widening inequality call for a profound shift in how we shape the places we live. But this shift won’t come from concrete alone. It must emerge from collaboration, material intelligence, and collective ownership.

To reclaim tomorrow, we must build greener, safer, and more regenerative communities—starting from the ground up.

Regenerating from the Ground Up

Local government regeneration teams are critical to this transformation. They connect a council’s vision with the lived experience of neighbourhoods.

Their work goes far beyond project delivery. It involves listening, engaging, and weaving together physical, social, and economic strands of urban life. It relies on forming resilient, inclusive partnerships, surfacing local knowledge, and unlocking potential through collaboration.

Regeneration done well becomes more than policy. It becomes civic practice.

Bamboo, Laterite, and the Material Logic of Place

Throughout West and North West Africa, bamboo grows fast, sequesters carbon, and regenerates naturally. It is abundant in regions from Ghana and Nigeria to Sierra Leone, Guinea, and parts of the Sahel.

Laterite, a reddish, iron-rich earth, is equally widespread—from the highlands of Guinea and Mali to Burkina Faso, Senegal, Niger, and as far south as Ogun State in Nigeria’s southwest. Once exposed, it hardens—making it ideal for blocks, walls, and floors with excellent thermal mass.

These materials are not rustic relics. These materials are regionally appropriate, climate-smart alternatives to cement and steel. They cool buildings passively. The materials reduce emissions. And they support circular construction economies rooted in local supply chains.

In arid or sandy zones where laterite is sparse, builders draw on clay, limestone, adobe, or stone—again adapting to context, not copying templates.

Architecture that Remembers

A city that forgets its people’s wisdom builds for no one.

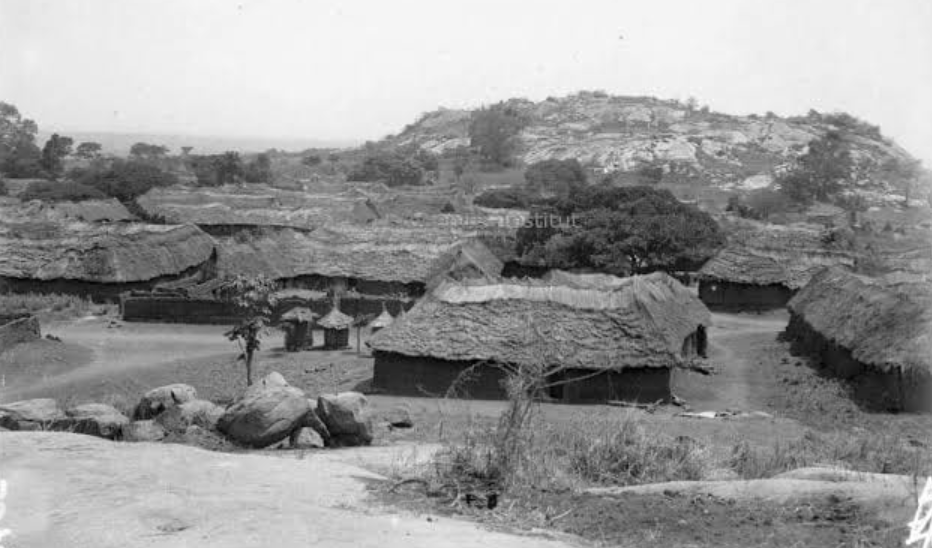

Across the region, indigenous and Islamic design traditions have long supported climate resilience and social cohesion. Yoruba agbo-ile, Hausa courtyard homes, Senegalese compound clusters, and Berber adobe structures reflect knowledge shaped by centuries of living in tune with place.

Participatory design taps into this deep memory. It gives space for people to shape buildings that breathe naturally, gather safely, and function communally—not through imported aesthetics, but through vernacular logic updated for modern life.

Here is a design that is not a return to the past, but a way to carry forward what still works.

Infrastructure for Social Life

Cities are not made only of buildings. They are made of relationships.

That’s why regeneration must support the full ecosystem of neighbourhood life: markets, tree-lined paths, small gathering spaces, communal water points. These are the acupuncture points of the city.

Urban acupuncture refers to small, strategic design interventions that create outsized benefits. A bamboo-framed street kiosk anchors informal economies. A clay-shaded corner becomes a micro-park. A composting toilet or water station—co-designed with women—restores dignity and daily convenience.

These gestures are not decorative. They’re essential. They regenerate social infrastructure with precision and care.

Co-Creation, Not Prescription

Real participatory planning is not extractive. It doesn’t gather feedback only to ignore it. Instead, it shares power, invites knowledge, and builds ownership.

Regeneration teams must work across council departments and alongside traditional authorities, youth groups, builders, and market women. In this model, elders bring memory, youth bring digital fluency, and artisans bring craftsmanship.

When local materials—bamboo, laterite, raffia, thatch—are prioritised, the benefits compound: carbon is reduced, skills are retained, and money circulates locally.

This is design as a tool for equity.

Build for the Climate, with the Climate

Every structure should respond to its environment. When it does, it doesn’t just use less energy—it supports human comfort, health, and resilience.

Thick laterite walls regulate temperature. Open courtyards draw in cooling breezes. Bamboo-framed roofs vent heat. Earth floors absorb and slowly release warmth. Together, these strategies reduce dependency on mechanical cooling.

Regeneration isn’t just about buildings. It’s about water harvesting, organic waste reuse, solar integration, and climate-adaptive layouts. It’s about systems that work with nature, not against it.

This isn’t a niche design preference. It is the only viable way forward.

Culture is the Code

Culture is not ornamental. It is structural.

Regeneration must root itself in the language of place—spatially, materially, and socially. This includes acknowledging community rituals, market rhythms, seasonal shifts, and faith practices in layout and use.

It also includes beauty. Because beauty matters—not as luxury, but as dignity.

When communities help shape their spaces, those spaces start to reflect their values. That is how neighbourhoods become legible, liveable, and loved.

Tomorrow Starts Here

Across West and North West Africa, communities are not waiting for solutions. They are already designing them—one classroom, kiosk, latrine, or market at a time.

But for this momentum to scale, urban policy must catch up.

Coming next: “Green Codes: How Urban Policies Must Evolve”

We will explore how planning laws, procurement systems, and building codes must shift to support participatory, low-carbon, locally led urban development.

Bamboo Urbanism: The Proven Way to Reclaim Flood-Prone African Streets

Not every African city began beside water. Many Sahelian settlements grew around wells, wadis and…

Human-Scale Neighbourhoods: The Proven Way to Build Strong, Sustainable Cities

Urban life thrives when its parts fit the human body and mind. Streets, squares and…

Bamboo Cluster Neighbourhoods: The Proven Way to Advance African Eco-Urbanism

Last week’s post revived sociability through human-centred streets. This post shifts towards the home. I…

Human-Centred Streets: The Proven Way to Reclaim African Urban Sociability

Every city tells a story through its streets. They reveal how people live, how they…

Biophilic Design: The Proven Way to Shape Sustainable African Communities

A city breathes when its architecture remembers nature. Too often, our modern buildings forget this….

Open-Source Urbanism: The Proven Way to Empower African City Builders

Urban design cannot succeed if knowledge remains locked behind bureaucracy. The tools of planning must…

One Response