The future city must not simply be built; it must be cultivated. It must feed itself, power itself, clean itself, and renew itself. And it must do this without extracting more than it can give back.

Rethinking the Foundations of Sustainability

Circular cities are cities that remember how to breathe.

At their heart lies a rethinking of urban metabolism – the idea that cities, like living organisms, have internal systems of input and output: food, water, energy, waste. But while most modern cities act like parasites – consuming without replenishing – a circular city is more like a forest: cyclical, layered, and resilient.

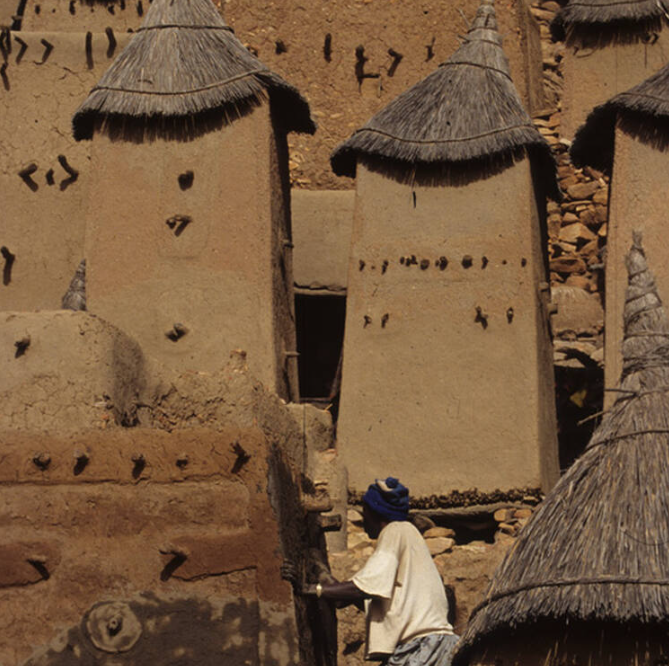

This is not an abstract ambition. Across West and Northwest Africa, circular thinking is already embedded in place-based traditions. Dogon villages on the Bandiagara cliffs harmonise with their sandstone terrain, layering function and meaning into every carved granary and sacred grove. In these highland settlements, water is caught, food is stored high and dry, and waste is returned to the earth as soil-building compost. The Dogon are not relics of the past – they are case studies in ecological continuity.

The Four Rs of Circular Design

In Yorubaland, the agbo ile – a form of inward-facing courtyard house – offered another vernacular solution. It captured shade, collected rainwater, ventilated through stack effect, and cultivated social cohesion. Waste became ash for farming, water cooled naturally in clay pots, and materials like adobe, timber, and palm frond were sourced from within walking distance. These structures responded to climate, not fashion, and worked with, rather than against, natural cycles.

Yet despite the elegance of such systems, urban design in recent decades has taken a linear turn. Cities have been conceived as machines of throughput: importing vast resources, exporting mountains of waste, with little regard for limits. The concrete tower and the glass box became icons of progress – regardless of whether they suited the place, the people, or the planet.

To counter this extractive logic, we must embrace the four Rs of the circular economy: reduce, reuse, recycle, and recover. These principles do more than divert waste – they shift the very DNA of design. A building is no longer just an object but a node in a living system. Its energy, water, and material flows must interact with those of its neighbours, forming metabolic loops that serve the whole.

Urban Metabolism: Cities That Feed Themselves

Consider water. In a circular city, rain is not runoff – it’s a resource. Roofs are shaped to capture it. Greywater from sinks and showers is filtered through plant beds and reused for irrigation or flushing. Courtyards double as micro-reservoirs. Local examples abound: Hausa houses with cisterns built into their cores, Sahelian settlements with seasonal basins that replenish aquifers beneath.

Energy too becomes site-responsive. Solar panels on shared roofs power lighting, charging stations, and even small-scale cooling. Organic waste is fed to biogas digesters, producing methane for cooking and nutrient-rich slurry for agriculture. Nothing leaves the loop unless it must – and even then, with thought.

Construction itself must also be re-examined. Rather than defaulting to concrete and steel – materials whose manufacture belches carbon and whose lifecycles rarely consider reuse – we must revalue what the land offers. Bamboo, long stigmatised as ‘poor man’s timber’, is fast-growing, structurally sound, and highly regenerative. When coupled with lime render or stabilised earth, it offers lightness, thermal regulation, and low embodied energy. Laterite, an iron-rich soil prevalent in West Africa, forms breathable walls that store heat by day and release it at night. Compressed earth blocks (CEBs), cured in the sun, eliminate the emissions of traditional kilns.

Courtyards and Climate Sense

This isn’t nostalgia—it’s necessary pragmatism. Nor is it about fetishising the local for its own sake. When used with care, even steel and concrete have their place. But their dominance must yield to a more diverse material palette—one rooted in ecological logic.

Crucially, the spatial layout of circular neighbourhoods must reflect this logic. The perimeter block becomes the basic unit: an arrangement of homes that enclose a central courtyard, shared but shaded, open yet protected. All exposure is directed inward; the external façade is more like a wall, with narrow hooded slots rather than broad, vulnerable balconies. This respects the security concerns of communities long accustomed to barricades, broken glass, and barred windows, while still allowing light, airflow and dignity. Safety, in such blocks, is achieved not through surveillance but through form – through belonging, familiarity, and layered thresholds.

Within these blocks, waste is sorted at source. Food scraps are composted. Paper and plastics are stored for repurposing or repair. Shared kitchens or kiosks facilitate collection, creating work, dignity, and cleaner streets. Each block becomes not only a living space but a metabolic hub.

The Myth of Western Innovation

Streets, too, must evolve. They are no longer just conduits for vehicles but public spaces for walking, talking, trading, playing. Narrower, shaded with native trees, punctuated by small squares and water points, they become the connective tissue of the circular city – binding not only buildings but people.

Importantly, circularity cannot be isolated from equity. A city cannot call itself regenerative while expelling the poor to its margins. Planning must be inclusive, with co-creation at its core. After all, circularity is not just a set of technical systems – it is a cultural practice.

It’s worth recalling that the narrative of innovation has too often been linear, westernised, and stripped of nuance. We’re often told that democracy began with Greece – a most peculiar democracy restricted to landowning men – as though Egypt, Persia, or India had never codified systems of governance or civic order. We hear of architecture as a European lineage, as if the stepped granaries of the Dogon, the city-states of the Yoruba, the domes of Persia or the sea-adapted structures of Micronesia never existed. We must disabuse ourselves of these flattened myths.

Circular Economies Are Not New

Knowledge travels and is shared through contact. Innovation is not owned. It emerges wherever people, materials, and needs meet with imagination. From the Aboriginal Australians who sourced water by reading rock hollows and plant signals, to the Austronesian navigators who crossed oceans by sensing waves and stars, there is a long global tradition of ecological wisdom. These are not curiosities; they are blueprints for survival.

In this light, the circular city is not a high-tech fantasy. It is a remembering. A gathering of wisdoms – some ancient, some still emerging – that treat the city as part of the ecosystem, not estranged from it. It cools without air conditioners, nourishes without imports, builds without waste, and thrives without harm. Such a city is possible. But only if we design it that way.

Such a city is possible, but only if we design it that way.

Up Next: “Bamboo in Disaster-Resilient Construction” – How regenerative materials can rebuild faster, safer, and smarter.

Enjoyed this piece?

Share it, subscribe for updates, or leave a comment with your thoughts on circular urbanism.

Bamboo Urbanism: The Proven Way to Reclaim Flood-Prone African Streets

Not every African city began beside water. Many Sahelian settlements grew around wells, wadis and…

Human-Scale Neighbourhoods: The Proven Way to Build Strong, Sustainable Cities

Urban life thrives when its parts fit the human body and mind. Streets, squares and…

Bamboo Cluster Neighbourhoods: The Proven Way to Advance African Eco-Urbanism

Last week’s post revived sociability through human-centred streets. This post shifts towards the home. I…

Human-Centred Streets: The Proven Way to Reclaim African Urban Sociability

Every city tells a story through its streets. They reveal how people live, how they…

Biophilic Design: The Proven Way to Shape Sustainable African Communities

A city breathes when its architecture remembers nature. Too often, our modern buildings forget this….

Open-Source Urbanism: The Proven Way to Empower African City Builders

Urban design cannot succeed if knowledge remains locked behind bureaucracy. The tools of planning must…

2 Responses