“Architecture is not the outcome of drawings but of lived choices shaped around place, ritual and rhythm.”

Cities across West and Northwest Africa are expanding fast. Too often, that growth flattens local identity, fragments community life, and intensifies ecological pressure. Yet it need not. The urban cluster offers a grounded alternative: compact, walkable, and materially rooted neighbourhoods that foster resilience and belonging.

Good urban design doesn’t shout. It whispers through shade, rhythm, proportion, and use; it saunters through courtyards and walkways; it luxuriates in arcades and water basins. These are the structures of memory, of ritual, and of daily life.

Clusters feel small enough to care, but large enough to function. They ease mobility, conserve resources, and make public life dignified.

They are not nostalgic throwbacks. They are the foundation of a livable, low-carbon future.

What Is a Cluster?

A cluster is a tight-knit spatial unit—typically four to six courtyard blocks. These are arranged around a shared square, a small market, or a shaded green. A school, church, mosque, library or town hall often anchors the core.

Infrastructure is decentralised. Power, water and waste systems scale to the neighbourhood. Roads are modest. Paths are shared.

Clusters are legible. People know where they are—and who they’re with. They invite stewardship, strengthen informal governance, and build trust.

Five block cluster (2 visible blocks) with public square and shared infrastructure

Low-Traffic by Design

Streets within clusters are quiet by design. Through-traffic is discouraged. Instead, small vehicles, handcarts, bicycles, and walking take precedence.

Main roads run along the edges. Inside, you find a sequence of shared lanes, pedestrian alleys, and shaded walkways.

The approach draws from places like the streets of old Kano—narrow, winding, and responsive to human movement. Comparable ideas surface in woonerfs (Dutch for “living streets”), which slow vehicles by removing kerbs and blurring the boundary between street and pavement.

This is not anti-car. It’s pro-life. Pro-child. Pro-community.

Public Life in Layers

Within clusters, public space unfolds in soft layers. Outer streets connect to the wider city. Inner alleys host play and pause. Courtyards serve both private rituals and communal gatherings.

Mosques, shrines or churches rest gently along these flows—not hidden, not dominant.

Colonnades frame movement. Verandas catch breezes. Shaded corners host elders. Squares become markets by day, prayer grounds at dusk.

These spaces don’t segregate life. They stitch it together.

Social life within and outside the block

Building with Local Logic

Laterite and bamboo are not poor substitutes. They are wise choices for hot climates, changing economies, and fragile ecosystems.

Laterite holds thermal mass, keeping interiors cool. Bamboo, when properly treated and compressed, offers lightness, flexibility and strength.

Together, they form an adaptable material palette. Walls breathe. Roofs overhang. Facades vary—textured laterite beside woven bamboo screens—while massing remains coherent.

Massing refers to the overall size, shape and arrangement of buildings. It’s how a cluster “sits” in space and catches light. Even with material variety, a neighbourhood can feel cohesive if the building forms—height, depth, orientation—relate well to each other.

Steel and concrete still serve—but sparingly. For anchors, not for walls. For load-bearing frames, not for entire neighbourhoods.

This isn’t about fetishising the vernacular. It’s about building what makes sense, materially and climatically.

Variations on the courtyard design

Past as Prologue

The cluster is not new. It’s a form that endures across geographies and histories.

Old Yoruba compounds showed how courtyards mediated family life, airflow, and ceremony. The streets of old Kano demonstrate how intimacy and public life can intertwine.

Igbo and Igala settlements arranged compounds around shared thresholds, fostering both autonomy and mutuality. The Mossi people of Burkina Faso constructed earthen villages that responded to climate, kinship and craft.

Elsewhere, Scandinavian cohousing and Danish courtyard housing repeat these same logics in modern form. The lessons are clear: the best urbanism is local, layered, and learned.

Making It Happen

Clusters don’t need to be delivered all at once. They work best in phases.

Start with a few buildings. Test one courtyard. Add shared infrastructure. Let it grow.

This means shifting from top-down imposition to co-creation. Local artisans, community members and small developers should shape form and programme.

Some clusters begin as informal upgrades—stealth projects that later knit into broader systems.

What matters is not scale, but care.

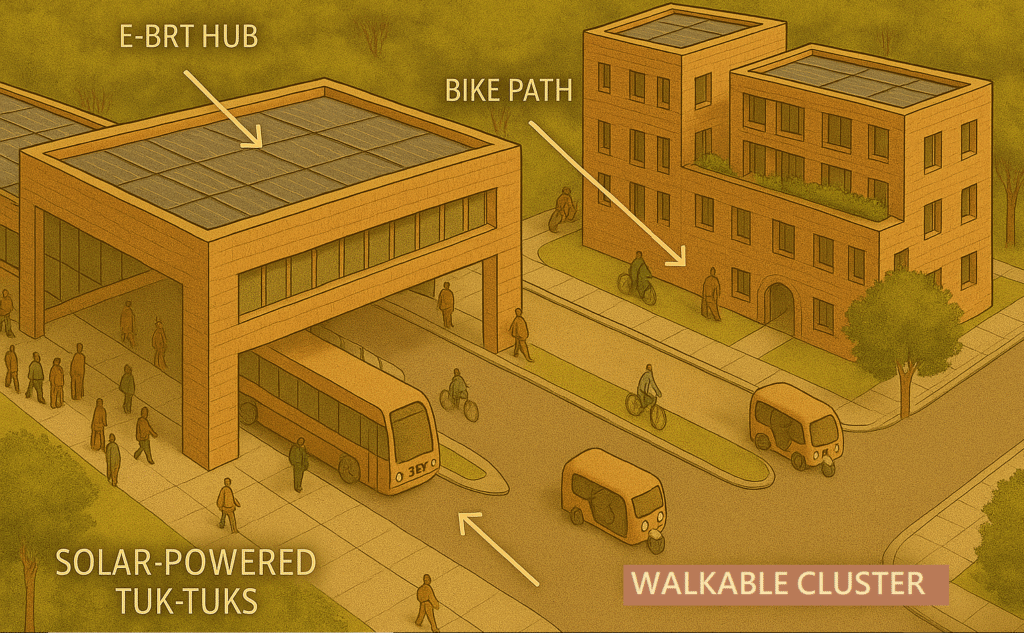

Cities do not need to sprawl to grow. They do not need highways to connect. They need finely grained networks—walkable paths, light mobility corridors, and interlinked neighbourhood clusters.

But in vast cities like Lagos, where distances between districts can stretch for hours, neighbourhood-scale alone is not enough. Human-scale planning must sit within a city-wide mobility framework that is clean, fast, and inclusive.

This means investing in electric bus rapid transit (e-BRT), light rail, water taxis, and safe cycling superhighways. Not as afterthoughts, but as the civic spine. Interchanges should land at the edges of clusters—not sever them—allowing people to walk or cycle the last stretch home.

Decentralised cities aren’t anti-infrastructure. They are just anti-overbuild. Infrastructure should serve life, not dominate it.

With the right balance of scale and grain, the cluster becomes not an island, but a stitch in the wider urban fabric—a city of neighbourhoods connected without compromise.

Next up: Circular Cities – How Food, Waste, Water and Energy Loops Reinforce Urban Resilience.

Let’s keep building with care.

Bamboo Urbanism: The Proven Way to Reclaim Flood-Prone African Streets

Not every African city began beside water. Many Sahelian settlements grew around wells, wadis and…

Human-Scale Neighbourhoods: The Proven Way to Build Strong, Sustainable Cities

Urban life thrives when its parts fit the human body and mind. Streets, squares and…

Bamboo Cluster Neighbourhoods: The Proven Way to Advance African Eco-Urbanism

Last week’s post revived sociability through human-centred streets. This post shifts towards the home. I…

Human-Centred Streets: The Proven Way to Reclaim African Urban Sociability

Every city tells a story through its streets. They reveal how people live, how they…

Biophilic Design: The Proven Way to Shape Sustainable African Communities

A city breathes when its architecture remembers nature. Too often, our modern buildings forget this….

Open-Source Urbanism: The Proven Way to Empower African City Builders

Urban design cannot succeed if knowledge remains locked behind bureaucracy. The tools of planning must…

3 Responses