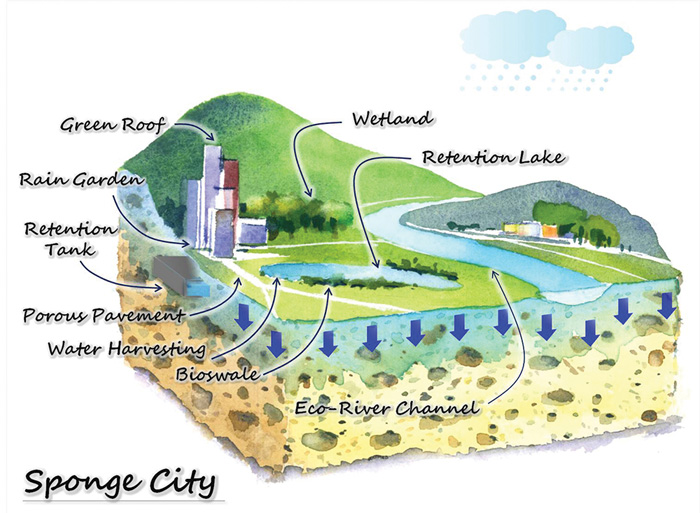

When rain falls in West and Northwest Africa today, it too often becomes a crisis. Streets flood within hours, homes are damaged, and businesses lose stock. The problem lies less with the amount of rainfall than with the way cities are built. Asphalt and concrete shed water instead of absorbing it, and drains, when present at all, struggle to cope. The result is predictable: chaos after downpours and dust during the dry season. A sponge city offers a different path.

At its heart, a sponge city is simple. Instead of rushing rainwater away, it captures, filters, and stores it. Streets are made more permeable so water seeps into the ground. Public squares are shaped to temporarily hold stormwater rather than being ruined by it. Courtyards, parks, and even schoolyards double as small reservoirs that later feed trees or supply handwashing stations. The principle is no different from a terracotta pot that slowly releases water to a plant: the city itself becomes a vessel for resilience.

The materials used in construction play a decisive role. Today, most buildings in the region rely heavily on concrete and steel. While durable, these materials are expensive, carbon-intensive, and often imported. By contrast, bamboo and laterite are abundant, renewable, and culturally familiar. Bamboo grows quickly, can be treated to last decades, and once laminated is strong enough for beams, roofs, and even bridges. Laterite — the reddish earth found across much of West Africa — can be compressed into blocks that regulate indoor temperature and reduce the need for air conditioning. Together, bamboo frames and laterite walls produce buildings that are both cooler and cheaper to run.

Other local resources strengthen this approach. Typha reeds, a common invasive plant in Senegal’s wetlands, can be turned into insulation panels. Palm timber, traditionally used in Yoruba and Hausa architecture, creates shaded verandas that keep streets walkable. Cork from North Africa’s oak forests — especially in Morocco and Algeria — provides renewable material for insulation and soundproofing where locally available. Granite and basalt, quarried locally, make long-lasting paving and kerbs. Using what is available reduces dependence on imports and builds regional pride in construction.

“Sponge cities in West and Northwest Africa are not futuristic fantasies but practical, locally grounded solutions. By pairing bamboo and laterite with time-tested courtyard design, they turn floods into reservoirs, streets into shaded networks, and public spaces into resilient community assets.”

For residents, the benefits of sponge-city design are immediate and tangible. Streets shaded by bamboo shelters and lined with trees are not just cooler but more welcoming. Markets raised slightly above ground level stay dry even after storms, protecting traders’ goods. Schools with courtyards that double as water gardens teach children about resilience while giving them shaded, green places to play. Public transport stops become gathering points under bamboo canopies, where captured rainwater cools the air with gentle misting. The city feels more humane, less hostile.

This is not a matter of nostalgia or architectural fashion. Courtyard traditions in Hausa, Yoruba, and Senegalese culture, as well as riad houses in Morocco, were always about managing climate. Thick earthen walls kept interiors cool, shaded courts created social space, and small pools helped regulate air temperature. These lessons remain valid. What sponge-city design does is bring them into the scale of the contemporary metropolis, combining old wisdom with new techniques.

Policies and planning rules need to make this shift easier. Building codes can recognise bamboo and earth block construction as mainstream rather than “alternative.” Regulations can encourage permeable surfaces and tree planting by reducing fees or offering fast-track approvals. Public works projects — schools, clinics, markets — should lead by example so that communities see how bamboo, laterite, and local fibres perform in real life. Training programmes for masons, carpenters, and bamboo processors will ensure quality and reliability, creating jobs along the way.

The outcome is not just technical resilience but a transformation of how people live in the city. Streets that no longer flood allow children to reach school safely. Cooler homes cut energy bills and improve health. Public spaces designed to absorb water double as community gardens or sports grounds. Cities become places that work with the climate rather than against it.

Climate change makes this transition urgent. Floods and heatwaves are intensifying, but the solutions need not be imported at great cost. They can be grown, quarried, and crafted close to home. Sponge cities built with bamboo, laterite, and other regional materials promise neighbourhoods that are not only safer but also more beautiful and dignified. In that sense, they are less an experiment than a return to the logic of living well within one’s environment.

Bamboo Urbanism: The Proven Way to Reclaim Flood-Prone African Streets

Not every African city began beside water. Many Sahelian settlements grew around wells, wadis and…

Human-Scale Neighbourhoods: The Proven Way to Build Strong, Sustainable Cities

Urban life thrives when its parts fit the human body and mind. Streets, squares and…

Bamboo Cluster Neighbourhoods: The Proven Way to Advance African Eco-Urbanism

Last week’s post revived sociability through human-centred streets. This post shifts towards the home. I…

Human-Centred Streets: The Proven Way to Reclaim African Urban Sociability

Every city tells a story through its streets. They reveal how people live, how they…

Biophilic Design: The Proven Way to Shape Sustainable African Communities

A city breathes when its architecture remembers nature. Too often, our modern buildings forget this….

Open-Source Urbanism: The Proven Way to Empower African City Builders

Urban design cannot succeed if knowledge remains locked behind bureaucracy. The tools of planning must…